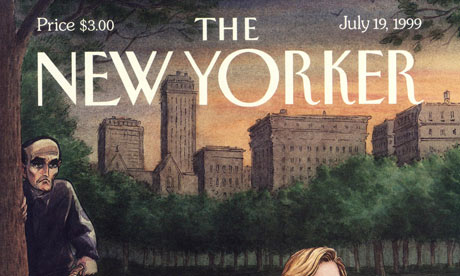

Martin Amis, Ian McEwan and Julian Barnes made a list of the best young British novelists in 1983; David Foster Wallace, Jhumpa Lahiri and Jeffrey Eugenides were named among the best American writers under 40 in 1999. Now the New Yorker has selected the 20 young writers it believes we'll be reading in years to come, with Jonathan Safran Foer, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Joshua Ferris and Wells Tower all making the cut.

The eminent American literary magazine will publish the '20 under 40' fiction writers it believes are worth watching in its Monday issue. Ranging from the 24-year-old Téa Obreht, whose debut novel will be published next year, to the 39-year-old writer Chris Adrian, the list is an eclectic mix of famous and lesser-known names, neatly dividing between the genders and providing readers with a guide to potential future literary stars.

The list, compiled by the magazine's fiction team, is restricted to writers who are from or based in north America.

"I was a boy when my family left the Soviet Union," said the award-winning Canadian author and filmmaker David Bezmozgis, 37. "We came to Canada with nothing and my parents had never heard about the New Yorker or most anything else. It seems strange and remarkable to me that 30 years later I would find myself on such a list.

"But then, it seems that a number of writers on this list are from somewhere else. So I suppose it means that the trend in American life is being reflected in new American writing."

New Yorker editor David Remnick said the list was "meant to shine a light on writers and get people to pay attention". "What matters is that someone pays attention to a writer they might not have known, and that they read – that's all I want."

36-year-old Philipp Meyer, whose debut novel American Rust was published last year, said it was "enormously validating" to be chosen by the New Yorker – though he admitted that such an exercise "seems very useful when you're the one picked, but if you are not picked, you need to ignore it completely."

Some acclaimed American writers just missed out by dint of age; Dave Eggers is 40, Aleksandar Hemon 45, Colson Whitehead 40.

"It's disappointing they didn't manage to find a space for Dave Eggers but I suppose that's their rules," said the Booker-shortlisted British author Philip Hensher, who was picked as one of Granta's best young British novelists in 2003, at the age of 37. Although he admitted that it made his publishing career "a bit easier overseas", he did feel that "these age-related things are a bit artificial".

The New Yorker list might include 10 women, but Hensher said that in general such line-ups can be "rather unfair to women novelists".

"There's a well-known phenomenon of the woman novelist who puts off her career, maybe to have children," said Hensher, "so she doesn't really make an impact until after she's 40 … a good example is Penelope Fitzgerald, who only emerged about five years before the first Granta list, and of course she was 60."

He suggested it might make more sense to select the authors "who have just emerged in the last five years", rather than basing it on age. "Novel writing isn't necessarily something that young people are very good at," he said. "I was 29 when I published my first novel, but I wish I'd waited."

Ben Okri, who won the Booker prize aged 32 for The Famished Road, said he felt lists like the New Yorker's could be "pretty dangerous".

"They're very helpful for writers and they are encouraging, and can identify future talents, but on the other hand sometimes they're too soon," said the author at the Guardian Hay festival.

"We will see in 10 years' time [how these authors have fared]. What matters is not the list but that mystical quality called genius – and a bit of luck."

Beijing-born Yiyun Li, who like two other authors on the list – Jonathan Safran Foer and Dinaw Mengestu – won the Guardian First Book Award, praised the New Yorker for including a host of short story writers in its line-up. "[That] means a lot to me, as I love stories, and it is always encouraging that The New Yorker treats stories and story writers seriously," she said.

Chris Adrian, 39

Daniel Alarcón, 33

David Bezmozgis, 37

Sarah Shun-lien Bynum, 38

Joshua Ferris, 35

Jonathan Safran Foer, 33

Nell Freudenberger, 35

Rivka Galchen, 34

Nicole Krauss, 35

Dinaw Mengestu, 31

Philipp Meyer, 36

C E Morgan, 33

Téa Obreht, 24

Yiyun Li, 37

ZZ Packer, 37

Karen Russell, 28

Salvatore Scibona, 35

Gary Shteyngart, 37

Wells Tower, 37

The eminent American literary magazine will publish the '20 under 40' fiction writers it believes are worth watching in its Monday issue. Ranging from the 24-year-old Téa Obreht, whose debut novel will be published next year, to the 39-year-old writer Chris Adrian, the list is an eclectic mix of famous and lesser-known names, neatly dividing between the genders and providing readers with a guide to potential future literary stars.

The list, compiled by the magazine's fiction team, is restricted to writers who are from or based in north America.

"I was a boy when my family left the Soviet Union," said the award-winning Canadian author and filmmaker David Bezmozgis, 37. "We came to Canada with nothing and my parents had never heard about the New Yorker or most anything else. It seems strange and remarkable to me that 30 years later I would find myself on such a list.

"But then, it seems that a number of writers on this list are from somewhere else. So I suppose it means that the trend in American life is being reflected in new American writing."

New Yorker editor David Remnick said the list was "meant to shine a light on writers and get people to pay attention". "What matters is that someone pays attention to a writer they might not have known, and that they read – that's all I want."

36-year-old Philipp Meyer, whose debut novel American Rust was published last year, said it was "enormously validating" to be chosen by the New Yorker – though he admitted that such an exercise "seems very useful when you're the one picked, but if you are not picked, you need to ignore it completely."

Some acclaimed American writers just missed out by dint of age; Dave Eggers is 40, Aleksandar Hemon 45, Colson Whitehead 40.

"It's disappointing they didn't manage to find a space for Dave Eggers but I suppose that's their rules," said the Booker-shortlisted British author Philip Hensher, who was picked as one of Granta's best young British novelists in 2003, at the age of 37. Although he admitted that it made his publishing career "a bit easier overseas", he did feel that "these age-related things are a bit artificial".

The New Yorker list might include 10 women, but Hensher said that in general such line-ups can be "rather unfair to women novelists".

"There's a well-known phenomenon of the woman novelist who puts off her career, maybe to have children," said Hensher, "so she doesn't really make an impact until after she's 40 … a good example is Penelope Fitzgerald, who only emerged about five years before the first Granta list, and of course she was 60."

He suggested it might make more sense to select the authors "who have just emerged in the last five years", rather than basing it on age. "Novel writing isn't necessarily something that young people are very good at," he said. "I was 29 when I published my first novel, but I wish I'd waited."

Ben Okri, who won the Booker prize aged 32 for The Famished Road, said he felt lists like the New Yorker's could be "pretty dangerous".

"They're very helpful for writers and they are encouraging, and can identify future talents, but on the other hand sometimes they're too soon," said the author at the Guardian Hay festival.

"We will see in 10 years' time [how these authors have fared]. What matters is not the list but that mystical quality called genius – and a bit of luck."

Beijing-born Yiyun Li, who like two other authors on the list – Jonathan Safran Foer and Dinaw Mengestu – won the Guardian First Book Award, praised the New Yorker for including a host of short story writers in its line-up. "[That] means a lot to me, as I love stories, and it is always encouraging that The New Yorker treats stories and story writers seriously," she said.

The top 20

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, 32Chris Adrian, 39

Daniel Alarcón, 33

David Bezmozgis, 37

Sarah Shun-lien Bynum, 38

Joshua Ferris, 35

Jonathan Safran Foer, 33

Nell Freudenberger, 35

Rivka Galchen, 34

Nicole Krauss, 35

Dinaw Mengestu, 31

Philipp Meyer, 36

C E Morgan, 33

Téa Obreht, 24

Yiyun Li, 37

ZZ Packer, 37

Karen Russell, 28

Salvatore Scibona, 35

Gary Shteyngart, 37

Wells Tower, 37

cropped.jpg)

.jpg)

cropped.jpg)

cropped.jpg)

2.jpg)

Cropped.jpg)

cropped.jpg)

4.jpg)